2010 City-Wide Open Studios weekend 2, Saturday

On the perfect Saturday of CWOS 2010's second weekend, I checked out the work of sculptor Gar Waterman and painter Joseph Adolphe at Waterman's West Rock Studio. In the front gallery, Waterman was showing a series of sea creatures, sculpted in onyx and marble. The walls were lined with landscape paintings Adolphe made during a sojourn to Italy this past summer.

Adolphe wasn't there when I visited but Waterman was. As always, he was an engaging, humorous and educational host. Waterman—whose father Stan Waterman is a renowned deep-sea diver and producer of underwater films—is presently trying to organize a traveling art/science exhibit around the subject of nudibranchs.

Don't know what a nudibranch is? (The word means "naked gill" in Latin.) Well, Waterman will be more than happy to share his knowledge of and affection for these sea creatures. He led several of us from the front gallery back into his studio for a seminar on the critters and the role they are presently playing in his art.

Waterman said nudibranchs are commonly known as "sea slugs" but that term was a misnomer.

"They are some of the most fabulous, colorful, exotic, wonderful, varied, strange creatures there are," he said. A type of gastropod mollusk like snails, "they evolved away from carrying a heavy calcium shell as protection to [using] chemical protection, because they are toxic."

Flipping through a book filled with pictures of the rambunctiously colored mollusks, Waterman noted that there are over 3,500 known varieties. Members of the diving community love them, said Waterman. They are particular favorites of underwater photographers, according to Waterman, "because unlike the bigger marine creatures they don’t move fast." A photographer can move in close with his or her macro lens and click away.

The group of bicyclists led by Devil’s Gear bike shop owner Matt Feiner showed up at that point and Waterman, like a carnival pitchman, declared, "This is the nudibranch production center of New Haven!"

"Who doesn't know what a nudibranch is? Raise your hand," said Waterman. As most hands went up, he responded, "Well, come in here and I will blow your mind!"

The ebullient host flipped through the pages of one of his books, showing off the images and explaining their physiology. He was particularly amused by the term "parapodal appendages," which refers to body structures some nudibranchs grow to protect their gill plumes. But he was serious too, noting that the creatures' toxins are so sophisticated that they are being studied for cancer research. Additionally, the nudibranchs are current indicators of marine health. They feed on coral reefs so an absence of nudibranchs could indicate problems with the reefs.

"There is a whole crazy world of people even nuttier than I am about these creatures," declared Waterman, referencing SlugJunkie.com, just one of many Web sites devoted to nudibranchphilia. (There is even a blog post about Waterman's sculptures at SlugJunkie.com.)

Like any good entertainer, Waterman knows he needs to give his audience what they came for and he didn't disappoint. He directed the group over to a piece in process to both show his version of parapodal appendages and explain his sculptural method. Waterman described how he will finish the onyx sculpture—already graced with lithe curves and protruding appendages—with selective polishing, leaving some areas rough for variety.

All his work, Waterman said, is nature-connected. In the past, he has created stone, wood and metal sculptures based on insect and seed forms as well as sea creatures. He showed the bicyclists a display case with seed pods that he uses for inspiration, noting with particular enthusiasm the ingenious design of the devil's claw seed pod.

After they left, I talked with Waterman about how he got started on his nudibranch "bender." As a diver, he said, he had loved them since he was a kid. But it was only within the past few years that he started working on realizing them in his sculptures.

The whole idea of a collaborative show for science museums arose out of a fundraiser a couple of years ago for a marine environmental group in Maine. The benefit was a celebration of his father's 86th birthday and 60 years underwater. Waterman recalled that in a bit of serendipity he saw a piece of stone that looked like a nudibranch.

"I didn't set out deliberately at the beginning to do what I'm doing," Waterman said. It's a way of pulling together all these pieces of his life, Waterman said: his years diving and growing up underwater, the people he knows through his father who are the "crème de la crème" of that scientific community and, of course, his art.

"To access that and take advantage of that is really fun for me," Waterman said. "And it's for a good cause—to raise awareness of the environment and biodiversity and what we stand to lose."

Because painter Joseph Adolphe wasn't there when I dropped by I couldn't speak to him about his paintings. But they spoke eloquently for themselves. Adolphe made all of them this past summer during a trip he took with a class he teaches at St. John's University in New York.

All the paintings were oil on board landscapes, specifically of ruins in Italy. Adolphe's approach, which involved liberal use of a palette knife, was wonderfully suited to the imagery. The painting surfaces are full of energy and texture—evocative of the crumbling facades of the ancient ruins—without losing a bit of their pictorial punch.

Across the street Frank Bruckmann was also showing paintings from a recent sojourn. Bruckmann's series of seascapes and shore images were all painted between January and August of this year in the isolated locale of Monhegan Island off the coast of Maine. Monhegan, according to Bruckmann, is accessible by an hour-long ferry ride an hour north of Portland.

Bruckmann said he and his family just "lucked out" in getting the rental for the extended stay. They have usually vacationed there in the summer or early fall. It was a treat for Bruckmann to experience the landscape at a different time of the year. He enthused about "the snow and the light on the horizon. Having winter light was just spectacular."

There was pretty much nothing to do but paint (and spend time with his family). Most of the painting was done outdoors on site in the cold with a little touching up in the studio.

The paintings "Cemetery" and "Whitehead" capture a dulcet combination of light and cast shadow. (I assumed the shadows were from clouds but Bruckmann corrected me.) The hues communicate the frigidity of the season.

Shadows also play a role in enhancing the dramatic impact of an untitled painting of Lobster Cove. The foreground is draped in shadows. The ocean is in the background behind an outcropping of rock. Bruckmann had planned to set up his easel and paint in the open meadow but the wind was so relentless that he moved back into a stand of trees for shelter. The benefits were aesthetic as well as physical. The foreground shadows cast by the trees contrast nicely with the winter sunshine on the brown brush in the middle ground.

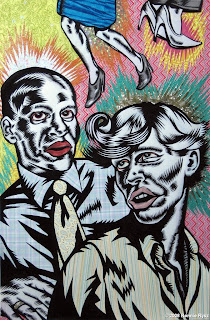

Ronnie Rysz's work has evolved quite dramatically over the past half decade. Visiting with Rysz in his 91 Shelton Avenue studio in New Haven, he pulled out a figure painting he made in 2005 while still in college. The small painting of a heavyset nude woman was done in a "classic progressive realist," as Rysz described it. It is accomplished but not striking. Rysz's current work, on the other hand, bursts with personality, style and graphic energy.

"I'm thankful for the skills I earned in school because without them I couldn't do what I'm doing now," Rysz told me.

Rysz was displaying a selection of mixed media paintings and prints—linocuts, woodcuts and multi-plate lithographs. His work synthesizes a wide range of influences: WPA muralists like Thomas Hart Benton, German Expressionism, Frank Stella, Pop Art master Roy Lichtenstein, graphic novelist Charles Burns and more.

His mixed media paintings generally start with a pencil drawing, usually referencing photographic imagery of random models drawn from video or film stills, advertising and other sources. From the pencil sketches, Rysz develops black and white drawings. He builds up layers with cutouts, adding color palettes, embossing. Along with canvas and paper, his mixed media paintings often incorporate wrapping paper, wallpaper, enamel and acrylic paints, industrial screening (which achieves a Lichtenstein-esque halftone effect), rhinestones, jewelry he's found and other found objects.

"It's a pretty involved process," said Rysz. "There are many, many layers of papers, painted papers, pre-made papers."

Losing All Touch, his most recent solo show, at the 22 Haviland Street Gallery in South Norwalk, dealt with the way digital media and social networking is alienating individuals from the physical proximity of direct communication. Many of the works shown in Losing All Touch were on display in Rysz's studio. According to Rysz, his subjects "are disconnected, aloof and distracted."

That the works are a commentary on the alienation inherent in online mediation of social relationships is not immediately obvious. It doesn't matter. Rysz's conception is just a further interesting layer to works that stand strong on visual appeal alone.

My final stop of Saturday was at Ben Hecht's studio in Hamden. Hecht was displaying charcoal figure drawings, paintings of military jackets and egg tempera paintings.

The series of military jackets was partially influenced by the presence of veterans of the current wars in the media today. But even more, Hecht was inspired by family members who served in the military. The jackets he was painting were the jackets of family members.

"When you are growing up, you learn that someone fought in such and such war," Hecht said. But what we learn about wars is often from the movies rather than directly from the (mostly) men who fought. Hecht said he built up a duality of reality and fantasy. "I deal with the reality of their experience in war through the artifact of their uniform."

Hecht noted that one of the paintings was of the uniform of his grandfather, a veteran of World War II. The duality of fantasy and reality has visual corollaries in the light used in that painting: warm and cool, natural and artificial.

"Part of the fantasy you have of the artifact is that that’s what they wore in action," said Hecht. "Then to hear from my grandfather that this jacket was what he was given when he returned, and he was several sizes smaller. Their real jackets were destroyed before they were shipped home."

Labels: Ben Hecht, City-Wide Open Studios, Frank Bruckmann, Gar Waterman, Joseph Adolphe, painting, Ronnie Rysz, sculpture, Stan Waterman

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home