Art that's under control

ALVA Gallery

54 State St., New London, (860) 437-8664

Two of a Kind: Carlos Estevez and Maureen McCabe

Ends Mar. 9, 2007.

The bats and balls are packed up and put away at the ALVA Gallery in New London. After December's American Legacies group show, this attractive space has cleared the bases for Two of a Kind, a challenging and attractive exhibit pairing Cuban artist Carlos Estevez with local artist Maureen McCabe.

In his artist statement, Carlos Estevez states that in his latest work he is "taking the metaphor of life as an ocean and our transit on it as a navigation." As an artist born and educated in Havana, Estevez has had a professional life buffeted by the pointless restrictions and indignities of residual Cold War politics. He has, since his first artist residency in London in 1997, led a nomadic life of residencies in cities ranging from New York to Dale, Norway and Boston to Paris.

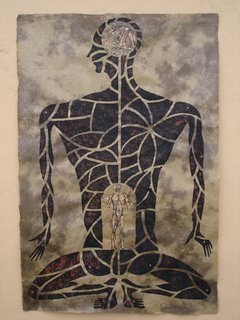

Estevez is represented with works that are either oil paint and pencil on canvas or watercolor and pencil on paper. They have mottled backgrounds akin to cloudy skies or murky waters. Stylized figures, often depicted with diagrammatic internal mechanisms, dominate the imagery: the self as a machine. The interpenetration of the human and the technological is a recurring theme.

In the watercolor and pencil work "Self-Navigation," a headless figure sits atop an elongated head that is flat like a mesa. This flat-topped head is a boat which its occupant propels with oars. Inside the head we see a contraption of gears and pulleys connected to the rudder and propeller. On one hand, the image represents agency or subjectivity—the individual choosing their own direction and applying the mechanisam of intellect to move. But at the same time, there is detachment. There are two separate systems, the physical and the intellectual.

This image, like many of Estevez's, shows the figure with rivets at the various j

oints, a marionette without the strings. This is a change from previous works in which strings did control the figures, although the force controlling the strings was not revealed.

oints, a marionette without the strings. This is a change from previous works in which strings did control the figures, although the force controlling the strings was not revealed.Here autonomy is a more problematic question. While there are no physical strings present, the individual is still subject to a network of external and internalized forces. For example, in "Inner Voices," the large, squatting figure contains two smaller figures. One stands in a hollow in the small of the back. He looks up at another desperate figure trapped in a womb-like chamber in the head. What is hinted at here is not internal conflict so much as a stifled desire for unity between mind and body.

This disconnect between mind and body is also an element in "Memory Pool" and "Avizorando el Porvenir" ("Watching the future"). In "El Síndrome de Adán y Eva" ("Adan & Eva's syndrome"), this theme gets a sly erotic twist. The nude male and female figures have their heads where their genitalia should be and vice versa.

In pieces like "Presente ausente" ("Absent-Present"), "Walking Universe," "The Ghost Tracker" and "Relaciones difíciles" ("Difficult relations"), the interpenetration of the figurative with the mechanical and architectural imagery suggests a self subject to something other than the straightforward control paradigm of puppet and puppetmaster.

In these paintings, free will—or, "self-navigation," if you will—exists within parameters of a system of impersonal forces. Individual action is inseparable from the physics of existence. This physics can be constraints of the natural universe, technological necessity or social strictures.

Maureen McCabe is a Professor of Studio Art at Connecticut College. Sh

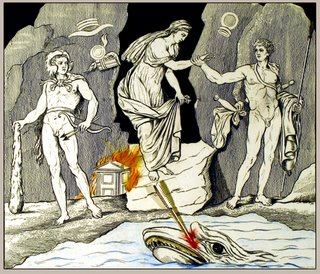

e is represented in this show by two separate series of work. Her Greek Series was inspired by Monumenti Antichi inediti, a mid-18th century book on the history of art by the German archaeologist and art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann. McCabe was specifically attracted to plates in the book depicting scenes from the writings of Homer.

e is represented in this show by two separate series of work. Her Greek Series was inspired by Monumenti Antichi inediti, a mid-18th century book on the history of art by the German archaeologist and art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann. McCabe was specifically attracted to plates in the book depicting scenes from the writings of Homer.She chose which images to work with based on three criteria—"story/theme, composition and the possibilities of added three dimensional objects." The latter element was of particular importance because McCabe's medium here is the box assemblage, a form of three-dimensional collage.

McCabe scanned the images at high resolution—her source was an actual antique book, not a reprint—and printed them on sturdy paper. She painstakingly cut them out and mounted them in front of of black or other colored backdrops. Selectively added elements—touches of gold or silver leaf, faux fur, small models of animals—heighten the visual impact of the original prints. There is a tiny toy dog in "Diogenes and Alexander the Great," an echo of the dog in the print, itself a symbol for Diogenes' philosophical cynicism. In "Sea Monster (Hercules, Hesione, Telamon)," faux yelo and orange fur is used to depict flames on a burning temple. Faux red fur is a bloom of scarlet blood, which flows from the arrow wound in a sea monster in the foreground.

Somehow, by cutting them out—extracting these images from their musty context—McCabe has breathed new life into them. Re-situated, the physical three-dimensionality of the images animates them with a life force.

According to McCabe's artist statement, there is commentary on the reverse of each piece, "densely layered with clippings, images and observations," that remarks on the contemporary relevance of these themes. She describes this as "a kind of hidden collage." Personally, I found it frustrating that this commentary was hidden, facing the wall.

Along with the Greek Series, McCabe is showing a half-dozen stately assemblages. These read like mysterious stage plays, hinting at narratives. In "The Black Cardmaster,"

the female figure on the slate background is decked out in a suit of cards. She holds a big paintbrush in one hand and wields a pair of scissors in the other. She looks toward an offstage character in the right foreground, whose presence is indicated only by a black-sleeved arm holding its own scissors in a white hand. Three blocks are stacked on the stage, with the symbol of one of the different card suits on each side.

the female figure on the slate background is decked out in a suit of cards. She holds a big paintbrush in one hand and wields a pair of scissors in the other. She looks toward an offstage character in the right foreground, whose presence is indicated only by a black-sleeved arm holding its own scissors in a white hand. Three blocks are stacked on the stage, with the symbol of one of the different card suits on each side.There is an overlap in these works with Estevez's enactments of external control. In McCabe's assemblages, individuals are subject, in some sense, to their place within a narrative. A character within a narrative may behave as though they possess free will. But the reins of the plot are in the hands of the writer.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home