Text messaging

ALL Arts & Literature Laboratory

Erector Square, 319 Peck St. Building 2, New Haven, (203) 671-5175

Texture

Ends Sept.16, 2006.

Incorporating text, letters and words into art isn't new but it has, over the past decade or so, become something of a postmodernist obsession. The exploration of meaning—or the concrete lack thereof—in language is fertile soil for intellectual play. And while literary theorists can spin out endless word-processed academese on the hermeneutics of the sliding of the signifier, artists can work the same ground with a broader palette and, probably, more fun.

"Fun" is not necessarily the first word that comes to mind with many of the works in the ALL Gallery's juried Texture show. But some coax a smile to go along with the intellectually furrowed brow. Caitlin Reuter's two life-size male and female figures, "Predator" and "Nymphet" (plaster, pigment, fake fur and enamel) comment on the way the construction of identity is inscribed in the body. In these cases, literally so. The man is bent slightly forward at the waist, his hands behind his head. His figure is under-painted blue, pink, green and yellow over which she has applied a coat of flat black. Carved into his back is the denunciation "Only God could love you for yourself alone and not your yellow hair." Incongruous fake black fur tufts form his armpit and pubic hair. The female figure, posed insouciantly with hands on hips, is over-painted with a mottled pink salmon color. Her shaved head is topped with a neon pink Mohawk of fake fur. "There are whip marks on his back but he loves me" is inscribed on her back. There is a serious point here about how words define who we are (or how we see others). How much can we imagine about these figures' "lives" through a single sentence? But that point is lightened with visual cues like the fake fur.

Julie Fraenkel's "(Self) Portrait," a charcoal and mixed media work, comments on the way individuals can use words-I believe the clinical term is "negative self-talk"-to undermine themselves. The central image is a drawing of a woman with short, dark hair. The drawing is worked over. And over and over. Her eyes fix the viewer. But her real gaze is relentlessly internal, reflected in layers of over-written text. The text reads as an internal monologue of a psyche in distress, overwhelming itself with criticism, self-doubt and second-guessing: "Make her head smaller. Change the shape here. This side is not as good. I need to remember to mention to ignore all the proportions." The fog of critical thought surrounds the woman. It transgresses all her physical boundaries and seemingly immobilizes her like a deer caught in headlights. A paralyzing solipsism. (Solipsitis?) But right in the center of the figure's chest, in darkest charcoal, is the redemptive statement: "She is not me anymore." It is either a work of courageous self-revelation or empathetic observation and imagination. The interior world made exterior in the form of the profusion of text distracts the viewer as it distracts the individual experiencing it.

There is a world's worth, and words worth, of anguish in Hollis Hammond's' "Hospital Stay." A large drawing, not quite life-size, it depicts a bald man reclining in a hospital bed with his knees slightly elevated. He is surrounded by the mechanical appurtenances of life in the hospital ICU: high-tech machines, tubes, IV's. Filling up the empty spaces of the image are words. Possibly the transcriptions of emails about "Pop's" condition, the text immerses us in a two-month diary of coping. The figure of Pop is central, the image around which the swarm of words marks the ebb and flow of his treatment, his snowballing complications and the mounting frustration of the writer.

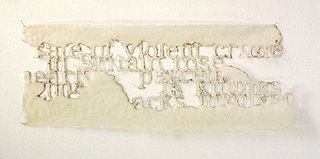

The working of memory is the subject of Donna Ruff's "Britain Rose." Ruff used a wood-burning tool to burn fragments of newspaper text into off-white handmade paper. According to Ruff, with whom I spoke at the show's reception on Sept.

9, the work is part of a series she did on various newspaper items that caught her attention. In this case, the excerpt is from a New York Times—recognizable by the distinctive font—story on crime and race in Britain. Ruff says she "wanted to give a few hints of what the story was about" without spelling it out. The edges of the letters are singed. The delicate nature of the paper causes the letters to curl in different ways, casting elongated fringed shadows. Bringing to mind the phrase "burnt into memory," it is a creative statement on how the mind processes information and, perhaps, the fragile and contingent nature of that process.

9, the work is part of a series she did on various newspaper items that caught her attention. In this case, the excerpt is from a New York Times—recognizable by the distinctive font—story on crime and race in Britain. Ruff says she "wanted to give a few hints of what the story was about" without spelling it out. The edges of the letters are singed. The delicate nature of the paper causes the letters to curl in different ways, casting elongated fringed shadows. Bringing to mind the phrase "burnt into memory," it is a creative statement on how the mind processes information and, perhaps, the fragile and contingent nature of that process.Two works explore the relationship of word to image (and both to "reality") from different angles. Ben Pranger's "Well-House" reads two ways. The paper is embossed with Braille text. The empty space where there are no Braille letters forms the suggestive outline of a house. Blind or vision-impaired visitors are encouraged to touch the work. In doing so, they can read the text, which quotes from Helen Keller's autobiography. According to information on the gallery's Web site, "In these 180 words, a blind reader receives more suggestive information than the viewer of the image."

Rachel Hetzel's two intaglio prints, "Jump" and "Fall," raise the question of which representation-word or image-best communicates a concept. Centered the near the bottom of each, in open space surrounded by black, are the title words. Above the word in each print is the silhouette of a figure engaged in that action. In the blank space defined by the outlines of the figures is text related to the word. Both word and image are ultimately abstract and neither are truly a "jump" or a "fall." How they ultimately relate to each other and to the real act is an arbitrary construction of language. Still, the dynamic figures could be more easily "read" across barriers of language.

If one picture is worth a thousand words, then how many words are pictures with words in them worth? Judging from the works on display at the ALL Gallery, a lot. (Although all this columnist can afford to spend are words of praise.)

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home