Central Connecticut State University: Samuel S. T. Chen Fine Arts Center1615 Stanley St., New Britain, (860) 832-2633

Painting with Fire: Agitprop Murals from Around the WorldFeb. 8—Mar. 10, 2007

Opening reception: Thurs., Feb. 8, 4—7 p.m.

Mike Alewitz wants a revolution in art. But Alewitz

also wants a revolution

through art. An associate professor of art at Central Connecticut State University,

Alewitz is a self-described Marxist "agitprop" artist and artistic director of the Labor Art & Mural Project. He is presently in the process of organizing an upcoming agitprop art show at CCSU,

Painting with Fire. The theme of the show: "They build walls between workers to create fear and break down solidarity. We paint walls to create solidarity between workers and break down their walls."

Painting with Fire

Painting with Fire will run from Feb. 8 through Mar. 10 in the Chen Gallery at CCSU. Among the artists invited by Alewitz are

Abe Graber, a 102-year-old

muralist,

CCSU faculty member Cora Marshall,

Boston muralist Dave Fichter and the

German group Farbfieber. Also invited is

Doug Minkler, a

silkscreen poster maker. A Minkler poster for the GI Rights Hotline is pictured here.

The call for participants invites the participation of those "whose art is created as part of the movement for social justice." Alewitz isn't just soliciting from professional artists. "Images may also be sent by political prisoners, active-duty GIs, striking workers and others who breathe life into our painting."

I had a phone conversation with Alewitz about agitprop and its relation to the larger art world.

According to Alewitz, contemporary agitprop (from agitation-propaganda) was born out of the Russian Revolution, "this moment where there was amazing ideas about taking art into the streets and decorating the streets and putting on mass performances.

"It's a tradition but like a lot of working class and radical history, it's kept hidden," says Alewitz. "The stuff I do is very based on that tradition."

Alewitz's work has been compiled in the book

Insurgent Images, co-authored by notable radical historian

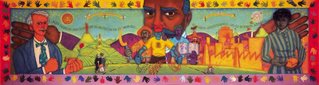

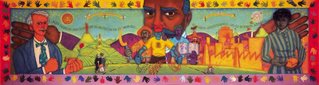

Paul Buhle. A prolific muralist, Alewitz has created images for numerous labor unions (a mural he created for a Mexican labor union is pictured below) and strike campaigns, as well as murals related to popular struggles in Palestine, Central America and Northern Ireland. He says most of his work "has been destroyed."

"I do political murals. I've had university administrators paint them out

, police vandalize them, fascists attack them. I've had union bureaucrats destroy them. I've had stuff that I've done internationally destroyed," says Alewitz. "I've stopped being surprised about it." In contrast, Alewitz notes that the faculty and administration at CCSU have been very supportive and respectful of free expression. "My students paint political murals all over campus and we have never had a problem."

While there are many artists who address political themes in their work, very few would describe themselves as "agitprop artists."

"There are some great political artists but mostly for gallery work," says Alewitz. "They do paintings about war, racism, the environment rather than try and integrate into movements themselves." Among the organizations invited to the show that Alewitz does consider to be engaged in genuine agitprop are the

Bread & Puppet Theater of Vermont and the

Beehive Collective of Maine. Both

Bread & Puppet and the

Beehive Collective often participate in demonstrations and use their art—street theater and narrative posters, respectively—to educate audiences about issues of class, imperialism, etc.

There is little support in the United States for public art in general, Alewitz says, and mural painting in particular. The funding isn't there. Toss in the element of anti-capitalist politics and it is that much harder.

Politically provocative images are "much easier to do in a gallery," he says. If some of the political images that will be in the upcoming show were "painted on a wall somewhere there would be a huge brouhaha."

"Art is a business, a vicious business. And as long as you are within the galleries, you are very much a part of a structure that's controlled by people in the art business," argues Alewitz. "If you have a private gallery, you have to produce work that's going to be bought by people with money. Generally, that's going to be work that flatters the rich or middle class. Even when the work is political or critical it has to be geared to people who are going to buy it.

"Public art, on the other hand, our audience, our viewers, are working people who don't have money. Our audience is the working class. We speak to them and for them. And that's very threatening to the powers that be, both within the art world and society at large," says Alewitz.

"If you paint a mural for meatpackers who are on strike and give this big public visual expression to something, it's very threatening. They'll destroy it. That's what happened to one of my pieces during a meatpacking strike in Minnesota," recalls Alewitz. "Workers are very marginalized in this society. You don't see workers on TV. There are no shows about workers. We only see them when they are portrayed as clowns or buffoons."

Does agitprop, which is born in service of a temporal political agenda, have any staying power as "art?" To answer the question, Alewitz returns to the agitprop produced in the early years of the Russian Revolution.

"There was a very brief moment during the early years where there was an enormous burst of creative stuff. It really transformed modern art in a lot of different ways. T

he idea was it was a revolution and you had to have new ways of seeing things and a whole new art," says Alewitz. "It gave birth to Constructivism, Suprematism and all these art forms that had a profound influence on the direction of art. All the Minimalist stuff we saw in the 50's was based on Constructivist work except devoid of its content." A Suprematism classic, El Lissitzky's "Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge" is pictured here.

The agitprop of the early revolution "did profoundly affect the art world even though it was of the moment," continues Alewitz. "I think things can be both and, to a certain extent, all art is. Cezanne's paintings of a bowl of fruit were very much of the time that he lived.

"Good art—one of the tests of art—is, does it live beyond the moment? That's why I find the Minimalism of the 50's vacuous whereas I find the work of agitprop Constructivist artists still fairly compelling even though you might be looking at a white square," Alewitz says. "The work goes beyond just the object itself. It's the idea and theater and context of everything that makes it live."

Besides seeking "banners, puppets and other large scale painting used on demonstrations, picket line, meeting backdrops, etc." for the exhibit, Alewitz is also inviting "groups and individuals to send small images that will be reproduced as banners by students in the CCSU mural program."

"At the closing, we are going to literally take the banners off the wall and have a march—an antiwar demonstration," says Alewitz. The closing will be on Mar. 10.

Given the tragic and criminal trajectory of the Bush administration—including its present urge to "surge" and destroy—such an artistic

and political statement couldn't be more necessary and timely.

Haven Public School's Comprehensive Arts Program, Breaking The Silence: Works by Imna Arroyo. Imna Arroyo holds an MFA from Yale University and is currently Professor of Art at Eastern Connecticut State University. Ms. Arroyo focuses on visualizing her identity, drawing on her indigenous and African Caribbean heritage. Utilizing multi-media, sculpture, and large scale hanging prints, Ms. Arroyo creates powerful and engaging works that address the Middle Passage slave trade and the spirit of her ancestors.

Haven Public School's Comprehensive Arts Program, Breaking The Silence: Works by Imna Arroyo. Imna Arroyo holds an MFA from Yale University and is currently Professor of Art at Eastern Connecticut State University. Ms. Arroyo focuses on visualizing her identity, drawing on her indigenous and African Caribbean heritage. Utilizing multi-media, sculpture, and large scale hanging prints, Ms. Arroyo creates powerful and engaging works that address the Middle Passage slave trade and the spirit of her ancestors.