Persistence of memory (as a theme)

Creative Arts Workshop Hilles Gallery

80 Audubon St., New Haven, (203) 562-4927

Memory, Mapping and Meaning: Christine Darnell, Sue O'Donnell & Kirsten Nelson

Ends Oct. 15, 2006.

The upstairs portion of the double-billed Creative Arts Workshop Faculty/Guest shows is Memory, Mapping and Meaning. CAW Sculpture department teacher Christine Darnell is joined by guests Sue O'Donnell and Kirsten Nelson in showcasing works informed by critical contemplation of the mechanisms of memory.

Kirsten Nelson uses architectural materials to create works that are both abstract and yet evocative of interior spaces. Each piece in this show, according to her artist statement, "evokes a recognizable site, yet it remains an invented fragment." Materials like wood moldings, sheetrock, plywood and wallpaper are part of the background noise of everyday life. In Kirsten's work, they are arranged to call attention to themselves.

In "Room Drawings," she has affixed to the wall 17 rectangular panels of varying sizes. Each is painted gray. Most are decorated in some fashion with small pieces of wood trim. Similarly, "Wall Structures" arranges cut pieces of unpainted wood molding on a wall in which Nelson has lightly drawn a grid with pencil. Nelson also has three other larger works in the show; although larger in size they are more minimal in content. All her works are austere and venture the idea of architectural space more by association than representation.

Sue O'Donnell has two different types of work in the show but both comment on the mechanisms of memory. Three pieces—"Throw," "Throw II" and "Run"—are series of blurry still images, probably video captures. They show a young girl being thrown in the air or running on a lawn. Interestingly, in the two "Throw" sets, we see a watch on the wrist of the person playfully (one hopes) tossing the girl in the air. Interesting because these are about time: chopping it up into discrete fragments, trying to store it imperfectly as memory. These aren't freeze-frame stills, however. Memories are never that exact. They are always fragmentary, hazy, and here the photographic imagery reflects that.

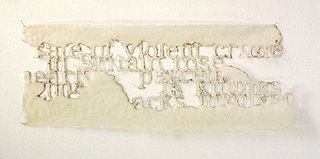

Her other works deal in text and graphing. The clever triptych "Relationships" is comprised of three ultrachrome prints. They purport to document states of mind like "Pressure, secrets and regret," "Fear, loss and hope" and "Faith, dreams and confusion" on a 40-year timeline. I should have brought my reading glasses for "Story Told II." Whatever the story being told in the rectangular block is, I couldn't read the excruciatingly small type. Which I suppose is the point. The story is real, but our limitations prevent us from recovering it. The charming "First Memory" is actually hundreds of interconnected memories. On a grid of black squares seven squares high by nine squares wide, O'Donnell has inscribed discrete memories within cartoon word balloons. Related memories are connected by little lines. Up close, the viewer gets involved in reading the numerous mini-narratives that flow together. Stand back and "First Memory" looks like a map of a white landmass, an island, in a sea of darkness.

Large charcoal and paper drawings and one floor installation (and an inkjet print that reprises the installation's idea) are Christine Darnell's entries. In the drawings "Table Mort" and "Birthday," objects on a table are meant to trigger memory-like associations. "Table Mort" is set with an electric mixer, an uncut birthday cake and slices of cake on plate, an electric fan, cut pieces of fruit, shoes and a skull. It must have been quite a party. In "Birthday," we see a plate with cupcakes, a birthday cake, a bowl and spoon, pitchers and an open book. The object lines cross each other like ghostly images. Nothing is opaque; nothing has a solid presence. Here, memories are phantoms.

The floor installation, "And What If After So Many Words...," is a three-dimensional work in rubber and plaster. Meandering lines of cursive writing are formed out of blue rubber. Standing on top of this text are two white child-size plaster feet. It is possible to make out some phrases in the textual cacophony, but they don't cohere into a comprehensible narrative.

Memory, Mapping and Meaning is a cerebral show, but not without a sense of play, particularly in Darnell's and O'Donnell's works. But I found Nelson's pieces, with their references to remembered interior spaces, less satisfying. While I appreciate the concept behind her work, I found the actual artworks somewhat devoid of emotional presence.