The Caveman Robot within each of us

John Slade Ely House Center for Contemporary Art

51 Trumbull Street, New Haven, (203) 624-8055

Jason Robert Bell: Tetragrammatron

Dec. 9—Jan. 21, 2007

Step inside the stately John Slade Ely House and glance to the right. There stands the imposing figure of Caveman Robot. And I can't but wonder: Is the gleeful crazed grin on Caveman Robot's face symbolic of Jason Robert Bell's disdain for the pretensions of th

e high art world?

e high art world?The 10-year retrospective Tetragrammatron, which was previously shown at Manchester Community College, offers an over-caffeinated comic book sensibility. Bell, working in an abundance of media, piles rampant lo-cult images one on top of the other. The walls are hung with large paintings but also lots of drawings and comic art pages. Scattered throughout the various rooms are abstract found object sculptures Bell calls "Trashures."

With a slightly different set of circumstances, Bell might have been an untutored "outsider artist," churning up a prodigious output for his own amusement and nothing more. According to his artist biography, he was "blessed with dyslexia" and "had the proverbial youth as an economically disenfranchised and misunderstood, yet talented outcast." But apparently Bell made the right impression on the right people. He got into and graduated from an arts high school in his native Houston, obtained a BFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and an MFA from the Yale University School of Art.

And he's painting furry Yeti women, constructing Caveman Robots and leaving Trashures on sidewalks.

It's not hard to see the appeal for Bell of Caveman Robot and Kala, Bell's rampaging and dreadlocked female Sasquatch. Both creations are noble savages, rooted in—but transcending—the primitive. Caveman Robot has the metallic, constructed body and the taillight-red eyes but he wears an animal fur and carries a big wooden club. Kala is big and naked; she attacks SUV's but also plays the harp. Then there's Bell, with his serious academic training and his love of comic books—"Lucifer in Reality" features blatant swipes from comics great Jack Kirby—and restless energy.

Caveman Robot is the joint creation of Bell and Shoshanna Weinberger. The character has been featured in Bell's self-published comic books (which can be perused at the exhibition). Adventures of Caveman Robot: The Musical, with Bell in the role of Caveman Robot, has been performed at The Brick Theater in Brooklyn, New York. There are photos of the performance on display at the Ely House. From the looks of them, the show has something of a Dada-meets-Rocky Horror vibe.

The imagery in the Kala paintings is raw and laced with comic book anger: bared teeth, flaring nostrils, violence. But at the same time, Bell evinces an exceptional affection for the materiality of paint and the emotional power of color. In the Kala works "Roar and "Kala Meets the Sun" and the non-Kala "Zeus Pater," Bell applies paint to the canvas with gleeful abandon. For "Kala Meets the Sun," painted this year, Bell used spray paint, acrylics and epoxy as well as oils to imbue the figure with a full measure of nobility. Paint is loaded onto the canv

as of "Zeus Pater," painted more than a decade ago. Smeared colors swirl together and form miniature landscapes. There is recognizable, if cartoony, imagery in this work. But "Zeus Pater" is better appreciated for its elements of abstraction.

as of "Zeus Pater," painted more than a decade ago. Smeared colors swirl together and form miniature landscapes. There is recognizable, if cartoony, imagery in this work. But "Zeus Pater" is better appreciated for its elements of abstraction.Bell often paints Kala raging in defense of a natural world under assault. In "Deer Death Man and Man Death Deer," two large canvases hung side by side, she confronts a hunter who has just killed a deer. As with many of Bell's paintings and drawings, there's a bit of folk artist in his approach. His depiction of the hunter is somewhat stiff. It's as though the academy-trained artist is at war with the primitive and the works represent an uneasy truce. "Kala Meets the Sun" is one of the more effective paintings in part because there is a fluidity to the rendering of her figure that is absent in many of his other works. It makes me wonder if in "Deer Death Man" Bell just didn't take the time to breathe life into the figure of the hunter. His output is prodigious but it would benefit tremendously by an emphasis on greater naturalism in his figures.

An anarchic sense of humor is found in such items as "Unicorn Turds for sell on Ebay." A pile of almonds painted with glitter is accompanied by a large lo-resolution digital image of the aforementioned magic feces. "Daily Back-Ups" presents 50 self-portraits. The punchline? They are all painted with oils on floppy discs. (And Bell did so in 1997, when floppys were still useful.)

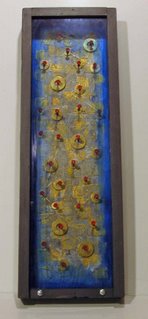

Then there are the Trashures. Bell makes spiky found object sculptures and installs—or "deploys"—them in public places. The Trashures shown at the Ely House are "undeployed." According to his Web site, the Trashures project began as a way to rid his studio of unfinished projects that were taking up space. But Bell became intrigued by the conceptual possibilities of the Trashures. As he writes on his Web site:

In the end these pieces are really about the shock of context. The Trashsures are objects that within a gallery would be objects to be look at and judged for aesthetic value. When placed on the street they are object that foster confusion. Every person that passes them has to choose what they are a piece of trash or a treasure.

With his artwork, Bell himself straddles the subjective line of trash versus treasure. He does so with considerable skill and self-awareness. Tetragrammatron is a notable and enjoyable show, not the least because it manages to take artmaking seriously without making "Serious Art."