Body of work

No Regrets Tattoo Studio

195 Rubber Ave., Naugatuck, (203) 729-3115

No Regrets Art Show

Closes Dec. 20, 2006

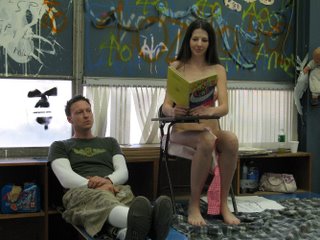

It's safe to say that No Regrets, Ink., a tattoo and piercing parlor in Naugatuck, is not your standard white cube gallery space. Heavy metal and punk rock music blasts out angry rhythms. The walls themselves are spray-painted to look like a stone castle, or dungeon. Fake metal gargoyles are perched on the parapets on the upstairs landing, overlooking the main room.

But No Regrets, open about three years, is hosting their first art show. The opening was on Nov. 17 and the show will up until Dec. 20. Many, if not most, of the participating artists are tattoo artists affiliated with studios around the state.

Where does this work fit in the conventional scheme of the art world? On the outside looking in, albeit with substantial indifference if not outright disdain. One major factor separating these works from what you might see in a gallery in New Haven is subject matter. Because as far as technique goes, some of these artists (not all—there is some dross here) are damn good at what they do.

Take artist Tim Harris, for instance. Harris' "Ladia del Muerto" features a skeletal hand clutching a pair of maracas, a couple of stylized skulls and a buxom beauty with puckered purple lips and face makeup that models a skull. Sweet! His "Miss American Pie" boasts a classic 1950's pickup truck kicking up dust, a cocked whiskey bottle and the proverbial farmer's daughter offering up a sloppy piece of pie and an eyeful of cleavage. Pulp fiction, for sure. But rendered in color pencil with such grace and facility as to achieve a certain kitsch transcendence. Similarly, his "Krylon Dreams" is a brilliantly executed color pencil drawing of a can of spray paint.

Similarly, Joe Capobianco—like Harris, a tattooist at Hope Gallery Tattoo—shows two over-the-top airbrush works, "Butchered Blue" and "Island Fever." They are pin-up girls of the 1940's refracted through the sensibility of contemporary tattoo culture. They are not a critique of pin-up art nor an ironic commentary. They are a celebration.

"Whatever's not popular in the modern art world, we tend to go in that direction. What separates us is it's deviant and we know that. It's deviant art," says Phil Young, a tattoo artist at No Regrets and one of the participants in the show. "The thing about a tattoo artist that's different is that we have to do anything. If someone wants a pig flying over New York City, we've got to draw that. We have to cater to any subject and put it in a style they like."

These days, with tattoo and body art having gone relatively mainstream, Young says there are more artists wanting to be tattooists.

"There's not really that many ways for artists to make a living today," says Young. And in contrast to the old days—like, say, the early 1970's—the tattoo scene is today "almost like a popular subculture, if that makes sense," says Young. It does.

Young's own "Baby Teeth," is a macabre oil painting of a young woman vampire. Her lips are smeared with burgundy blood after biting into a Barbie doll she holds in her hands. It's bizarre. "Baby Teeth" could be a 1930's pulp magazine cover, with its dramatic red backlighting. It might look out of place in the Yale University Art Gallery. But is it really more bizarre than revered religious art of the Middle Ages or Renaissance? Than surrealism?

Christian Perez's "Blood Bath" is a cartoonish political commentary. A porcine figure in a gas mask lounges in a sea of scarlet blood, pouring a beaker of blood over his bloated belly. Subtle? Not so much. He wears American flag briefs. The tip of a missile protrudes from the sanguineous sea. It is a color pencil drawing on board mounted within a black box frame. Bullets, pointing inward are affixed to the frame edges. Perez works at Lovecraft Tattoo in New Haven.

Chris Uminga's "Ben Sasnoff," is an ink and watercolor drawing of a waif, like the large-eyed children of motel room infamy as imagined by a cross between the Cartoon Network and Chiller Theatre. Uminga, a comics artist with his own creepy, fluid style, has painted his creation with pointed horns and elf ears and a big open white face with dark circles framing blank yellow eyes.

Whatever his intention, Marc McChesney's "Crucifixion" is deeply affecting in its representation of the agony of Christ. The figure is contorted on the cross, mouth wide open in screaming pain. McChesney's energetic brush work and coloration are filled with wonderful collisions of freeform abstraction. He has a true affection for color. Another painting on panel, "Harem (Figures)," works in a rainbow of colors in the background. On top of that, he has used black and white paint to sketch gestural female nudes.

Among the standout works are Ericka DeVoid's dolls, displayed in a glass case. According to Phil Young, DeVoid was inspired to try making dolls by seeing dollmaking on a Martha Stewart TV show. But DeVoid's dolls are not cute, homey Martha Stewart Living objects. They are more akin to the characters that populated filmmaker Tim Burton's The Nightmare Before Christmas. "Rita Mortis," a goth doll with attitude, has the phrase "Bite Me' spelled out on her fingers. Her full-length leather dress has two front seams held together with safety pins. A bent nail pierces her nostrils and obvious baseball-like stitching arches over her forehead.

Also in the display case are samples of two very different types of artwork by No Regrets owner Rob Gramlich. There are a couple of surreal Photoshopped digital collages, which are nicely done. Even more impressive are the two clay sculptures, in particular "Three-Eyed Snail." Gramlich sculpted the snail and its base out of clay, painted the entire work and then coated it with a shiny glaze. Sure, there's a strong element of subcultural kitsch to it but it's also lively, well crafted and convincing.

This is the realm of skulls and snakes and blood, faces twisted in anguish or shrunken in alienation. Perhaps it's not the "Garden of Earthly Delights", but it's certainly an imaginative world in which Hieronymus Bosch could feel at home.